The REAL Jumper's Knee

Many athletes deal with the condition known as "jumpers-knee" which is pain or inflammation down at the bottom of the knee.

Any time you see an athlete wearing a knee strap they're wearing it or this form of patellar tendonitis. The strap takes pressure off the patellar tendon and tends to lesson the pain.

One mistake I think a lot of therapists, sports mds, coaches, and athletes make is not differentiating between different types of patellar (knee) tendonitis. I don't consider myself a therapeutic expert but this is just something I've noticed over the years. Oftentimes any sorta knee pain gets dumped into the category of "patellofemoral pain" or "jumpers knee." Technically when someone refers to patellar tendonitis they're referring to the common lower knee pain.

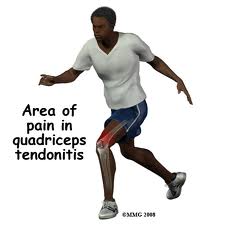

However, tendonitis of the knee can actually manifest as either pain towards the bottom of the knee or pain near the top of the knee. The kind with the pain at the top of the knee is what I refer to as the REAL jumper's knee. This picture illustrates the common point of pain.

the pain is often right under the very top of the knee cap. Technically this type of tendonitis should be called "superior" patellar tendonitis or quadricep tendonitis.

How Does Tendonitis Develop?

What happens in any form of tendonitis is the tendon becomes inflamed due to microtearing. If the microtrearing continues long enough the inlammation will subside and the tendon will begin to degenerate. Most CHRONIC cases of tendonitis don't involve inflammation, just pain, and should more accurately be called tendinosis.

But anyway, here's why I say the upper knee tendonitis should actually be called the REAL jumpers knee:

For one thing it's more common in people that actually TRAIN to jump by training with proper strength training and plyometrics. In my experience the "normal" type of lower patellar tendonitis is most likely to occur in non strength trained athletes. In fact one of the most effective treatments for it is strengthening the quadriceps. In contrast, superior patellar tendonitis usually occurs in people that strength train regularly while simultaneously engaging in explosive jumping activity.

The perfect recipe to develop it is:

1. high levels of quadricep strength (regular squatting or solid barbell training)

2. high or intermmitent levels of explosive jumps

3. low levels of cardiovascular, GPP, or conditioning activity

4. low levels of static and dynamic mobility work - flexibility deficits

5. Advancing age

Strength training can be implicated because as the quadriceps (particularly the rectus femoris) get stronger they pull on the front of the knee which, in the absence of proper mobility work, puts some strain on the quad/knee attachment point. More often than not in my experience this condition occurs in people that already have quite strong legs, particularly quadriceps. Since most people don't naturally have extremely strong and powerful legs it's normally a condition that occurs after an athlete has been training for a period of time. Anyhow, when you have very strong quadriceps, limited mobility work, and then engage in very powerful activities (like explosive jumps) that strongly engage the quadriceps you increase the strain at the quad/knee tendon at least 10 fold. When you combine that up with low levels of cardiovascular type activity you don't get much intermittent collagen building blood flow into the tendon. Put all those things together and you have a recipe for upper knee pain.

For some reason this condition also seems to affect aging athletes moreso than youngsters. In fact I can't count on 1 hand the number of athletes under the age of 21 I've known who've had it, most of them are a little older. I believe it's due to the fact that as an athlete ages they typically get significantly stronger less mobile, and tend to engage in less overall "outside the gym" activity.

The Prognosis

Unfortunately, in my experience, prognosis for this type of knee tendonitis is not as good as the other. It's not as easy to work around and can sometimes take YEARS for it to go away, if at all. It's actually the injury that ended Mark McGwires career. He had surgery to repair it but that still didn't get the job done. I know a few other people that have dealt with it for years. I personally dealt with it twice over a 6 year period of time and was once virtually out of commission for almost 2 years. Granted, I didn't lay off of it like I should have which is why it took so long to go away. But for the better part of 2 years I was in so much pain I couldn't do any sorta quadricep dominant squat AT ALL and any jumps I did hurt like hell and would ofen send me writhing to the ground in pain. That's fairly typical for this condition. It hurts but people gut it out and it gets worse.

What You MUST Do

If you ever begin to get this type of knee pain there are 3 things that you MUST do:

1. Eliminate ALL forms of quadricep training that cause ANY pain

Any activity you do that causes or recreates the pain must be eiminated. Unfortunately that means squatting is usually out. (This is in direct contrast to lower knee tendonitis which typically is HELPED by quadricep strengthening.)

2. Eliminate ALL jumps

There's no way to get around this. Jumping is usually the one activity that causes the most pain. If you jump with this condition you're practically guaranteeing yourself a chronic condition and you WILL be in constant pain. Trust me, I know. It WILL NOT respond to treatment unless you totally eliminate jumps and plyos. The ONLY jumps you might be able to get away with are jumps in a pool - even then I'd be very careful. This is the type of condition that you can make weeks of progress on but the MOMENT you do something stupid and flare it up again you start right back at zero.

3. Do LOTS of quadricep and hip flexor stretching

Static stretching the quads and rectus femoris is particularly helpful in my experience. As noted above, the tighter your quads get the more your quad tends to pull on the knee attachment point. Over time this causes strain. The issue is compounded many times because people disproportionately strengthen their quads and disproportionately STRETCH their hamstrings. Think of the quad/ham ratio sorta like a pulley. the quads pull from one side and the hams from the other. Most people do at least a 2:1 quad to hamstring strengthening protocol and a 2:1 hamstring to quad STRETCHING protocol. Not many people stretch their quads like they do hamstrings and when done in conjunction with a quad dominant program that's just asking for an imbalance and eventual knee pain.

Anyway, the more often you stretch your quads thebetter. I'd go twice a day to start and I'd also make sure I hit the other major lower body muscles - calves, hamstrings, etc. Both static and dynamic mobility work are beneficial but if you have to choose one or the other go with the static.

4. Regularly engage in regular, non-irritating, rhtymic activity. Walking on a treadmill, jump rope, cycling, flopping your legs in a pool, bodweight GPP circuits - pretty much any activity is fair game. This increases blood flow to the tendon which helps with new collagen synthesis. I'd go with a minimum of three 20-30 minute sessions per week.

Eccentric Protocols

One thing people may be curious about are eccentric protocols, which have found to be valid for some types of tendonitis/tendonisis. For example, someone with achilles tendonisis might do negative singe legged calf raises taking 6 seconds on the negative. The eccentric contraction is though to contribute to microtearing which leads to remodeling and healing of the tendon. Unfortunately, in my experience this form of injury doesn't respond well to it. The negatives are more apt to flare the injury up again, erasing any progress made.

For strengthening movements it's imperative you eliminate any activity that recreates pain. That usually means ALL squatting movements are out. You MIGHT be able to do wide stance box squats - sitting back on a box, but if it irritates your knees don't do it.

With regards to strength movements there are a few things to consider:

Jumping is a gross movement pattern involving a combination of ankle extension, knee extension, and hip extension. How much each muscle (or joint) contributes can vary somewhat depending on the individual, but the good thing is it's possible to somewhat change the relative contributions of each. If you have any knee pain chances are you're already getting more than enough knee extension in your jumps, so you want to focus on getting more hip and ankle extension. How do you do that? Simple.

1. Optimize your pelvic posture - establish optimal femoral control

2. Get strong in the right places, which typically means the glutes

3. Pay attention to your feet

4. Get mobile in the right places.

This article does a pretty good job explaining what to do.

As you get strong and mobile in the right places you will probably notice the "feel" of your jump changes, at least when you go back to jumping. It'll usually change for the better. It may not necessarily be higher but will feel smoother and you'll come off the ground easier with less stress on your knees. The key is maintaining that recruitment patten permanently while strengthening the entire kinetic chain (hips, knees, ankles) from that point on. More hip involvement means better leverage and less stress on the rest of the kinetic chain when activating concentrically, so you'll be less prone for more knee pain down the road.

It also wouldn't be a bad idea to incorporate some type of soft tissue work for your entire lower body from your beltline on down. Deep tissue massage type work is ideal but if you don't have access to one rolling around on a foam roller, basketball, medicine ball, or lacrosse ball will do some good.

Diet and Supplements

Some people swear by supplements like wobenzyme and fish oil for tendonitis. Wobenzyme is a form of digestive enzymes that aren't taken for digestion. The enzymes are specially coated to survive digestion. The get in the bloodstream where they're purported to "gobble up" inflammation causing irritants. They have been shown to reduce inflammation in some cases. Fish oil will also reduce inflammation. I know people that have had GREAT success with wobenzyme and fish oil but in my experience not everyone responds. I think the main reason for this is many tendonitis conditions don't involve any inflammation at all - just pain and tendon degeneration. In my experience if you have an inflammatory type of tendonitis with redness and some swelling you're more likely to be helped by anti-inflammatory supplements and special diets. At the diet end the most important thing for collagen synthesis is get enough protein, carbohydrate and overall calories. L-glycine in the form of two 5 gram doses per day may also help as it's direclty involved in collagen synthesis - it's great for joints too. It's cheap as heck and worth a shot. I wouldn't expect a DRAMATIC difference, but you might notice some benefits.

Conclusion

Fortunately in my experience once you get your progress on the right track, which means avoiding ANY and ALL activities that cause irritation, the injury responds relatively quickly. If this is a problem you have already or you BEGIN to feel coming on follow this advice and within a week or 2 you should see a significant difference. Once you can jump or squat without pain you should be good to go. Once you're healed up and back to normal one thing that will be particularly beneficial in the future is you need to make sure you ALWAYS stretch your quads and rectus femoris after strength work - even if it's only one 30 second stretch it will go a long way.

Good luck!

-Kelly